[1] Cf. Börste, Norbert/ Santel, Gregor G.: Schloss Neuhaus bei Paderborn, Berlin 2015, p. 38f.

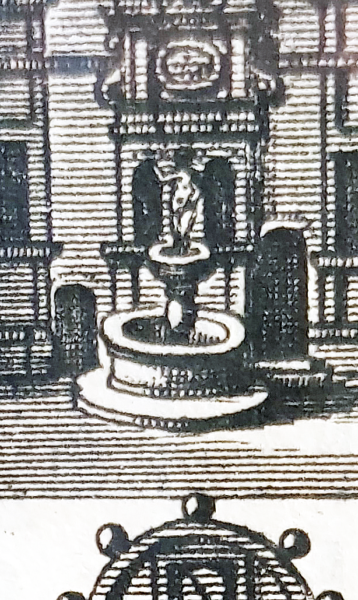

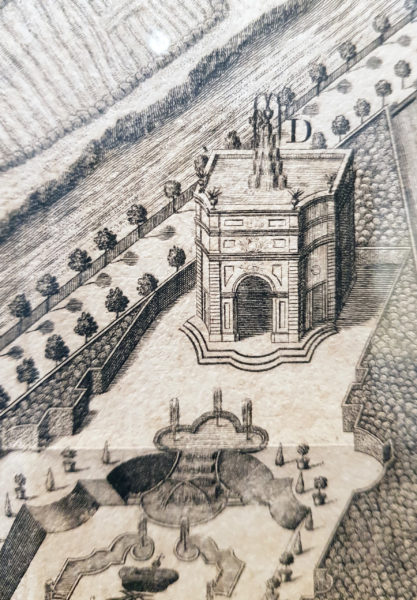

[2] A contemporary illustration of the double-shelled fountain with figure can be found a. o. in the „Monumenta Paderbornensia“ of Prince-Bishop Ferdinand von Fürstenberg (1669/72).

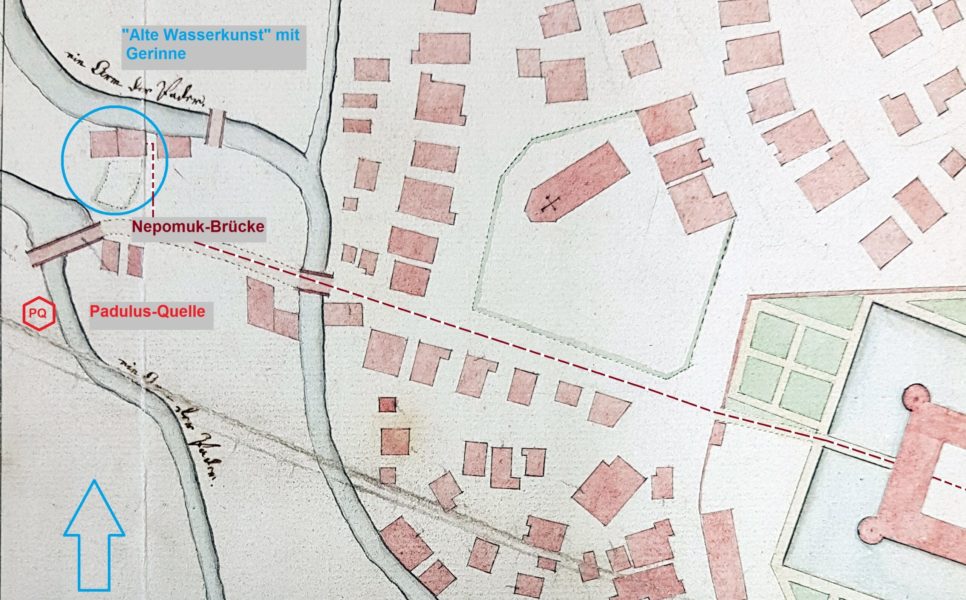

[3] Thus, the recent assumption in the literature (2015) that the „old waterworks on the Wasserkunstpader“ were responsible for the „operation of the fountain“ in the baroque palace garden must be critically questioned. Cf. Börste/Santel, Schloss Neuhaus, p. 79. There is also no concrete evidence for a later construction of „waterwork[s]“ under Prince-Bishop Dietrich Adolf von der Recke (officiating 1650-1661) after the Thirty Years’ War. Cf. Wurm, Neuhaus, p. 41.

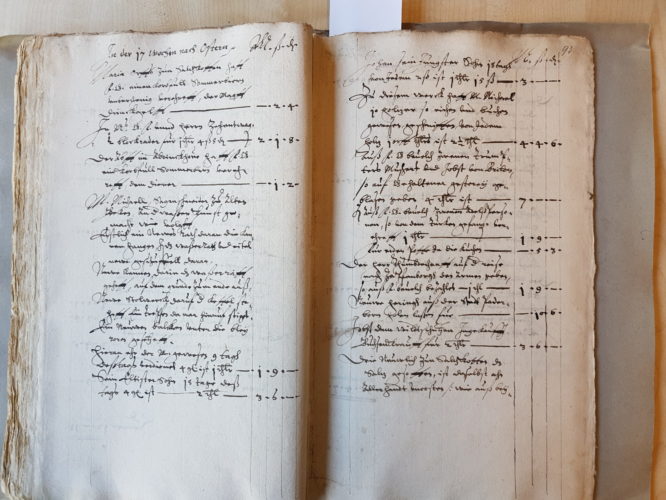

[4] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Ämterrechnungen Neuhaus (1596/97), Nr. 1046, fol. 92v-93r.

[5] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Ämterrechnungen Neuhaus (1596/97), Nr. 1046, fol. 92v.

[6] Cf. Neuheuser, Heinrich: Geschichte der Gemeinde Altenbeken, Paderborn 1960 (ND 1989), p. 20-24.

[7] The Altenbeken sawmill probably stood in the lower village. In an ecclesiastical visitation report of 1655, a „Sagemüller“ is located there. Cf. Neuheuser, Altenbeken, p. 149.

[8] Periodic transports of wood to Neuhaus were part of the princely „Spanndienste“ (service using draught animals) for numerous farmsteads in the village of Altenbeken. The obliged peasants not only had to transport the timber with their own horse-drawn carts, they also had to cut the wood themselves in the Egge mountains. Cf. Henning, Bauernwirtschaft, p. 125f.

[9] For this subsidiary office he was paid 2 Reichstaler annually by the Rentmeister. Cf. Ämterrechnungen Neuhaus (1663/64) and (1672/73), no. 1072 and 1081, LA Münster, fol. 129v; 146v.

[10] Partial account, 5 May 1758. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 31r.

[11] Cf. Börste/ Santel, Schloss Neuhaus, p. 75.

[12] Cf. Hansmann, Wolfgang: Der Neuhäuser Schlossgarten (1585-1994) (Studien und Quellen zur Geschichte von Stadt und Schloß Neuhaus, Vol. 2), Schloss Neuhaus 2009, p. 115-160, here pp. 131.

[13] Partial account, 19 June 1758. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 29r.

[14] Partial account, 23 October 1758. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 24r.

[15] Partial account, 20 November 1758. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 23r.

[16] Partial account, 20 November 1758. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 23r.

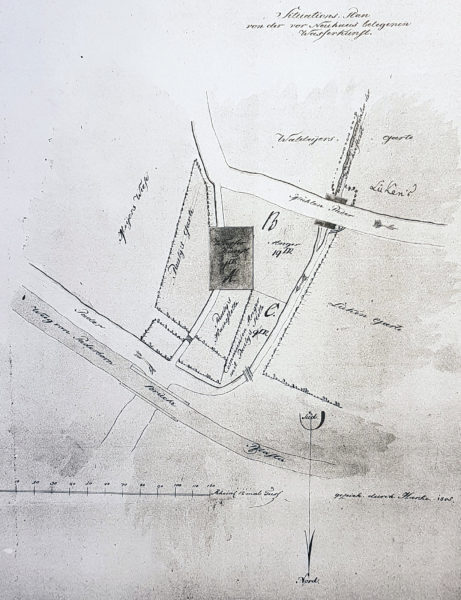

[17] Copy of the contract of sale, Neuhaus 28 October 1805. LA Detmold, M 1 I U, Nr. 660, unfol.

[18] Cf. LA Münster, Kriegs- und Domänenkammer Münster 16/324.

[19] In 1851, the Old Waterworks building was probably no longer standing. A Prussian surveyor describes the property „on which a waterworks building had been erected and put into operation in the past“ as undeveloped. Cf. assessment by the Prussian building inspector N.N., 15 June 1851, LA Detmold, M 1 I U, No. 660, unfol. On the Prussian „Chaussée“ map of the „Bauconducteur Leopold“ of May/June 1836, the building of the Old Waterworks is no longer marked. Cf. StadtA Pb, M 5-11 No. 95.

[20] Cf. Report of the „Landrätlicher Kommissar“ zur Mühlen to the district government Minden, 10 September 1849. LA Detmold, M 1 I U, No. 660, unfol.

[21] Cf. technical report by the Prussian building inspector N.N., 15 June 1851. LA Detmold, M 1 I U, No. 660, unfol. According to the expert, the „kleine Ringgraben“ (small ring ditch) divides „into the right arm the castle moat /: called the Graft:/ from where the water flows into the Lippe; in the left arm, however, cleans the privies of the barracks and from there also flows into the Lippe above the mouth of the Alme.“