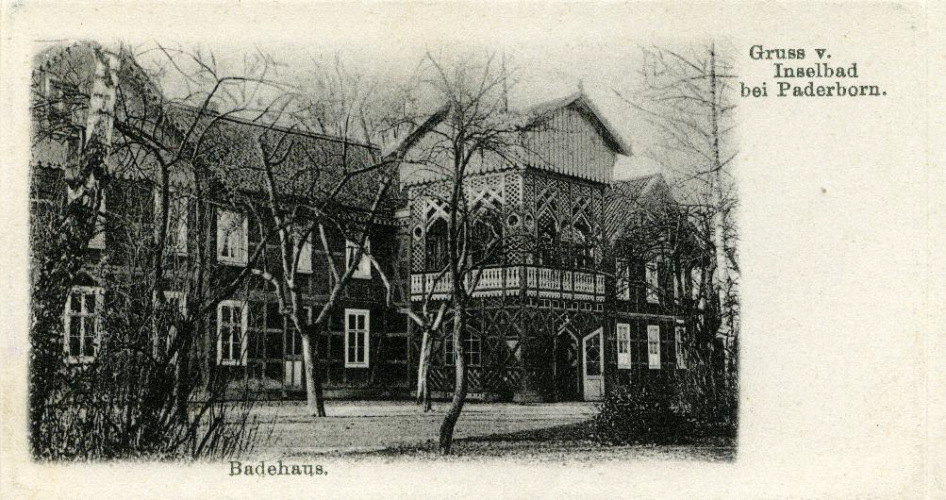

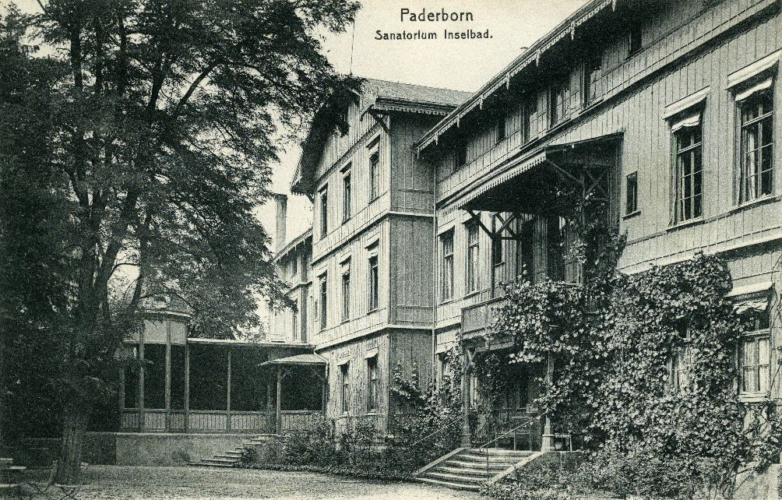

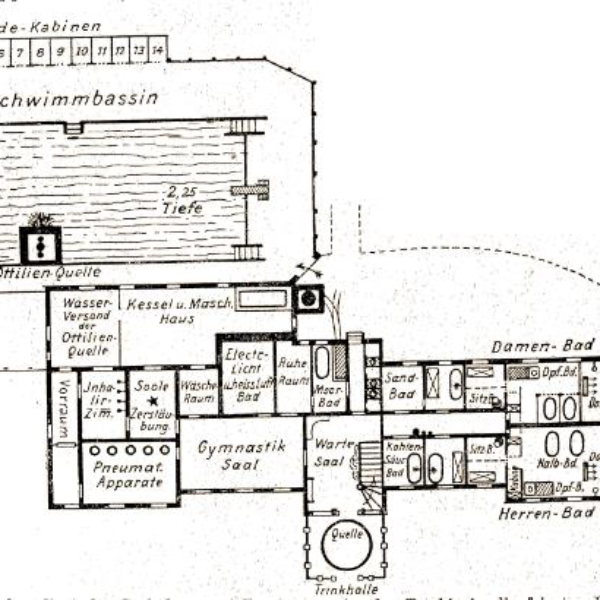

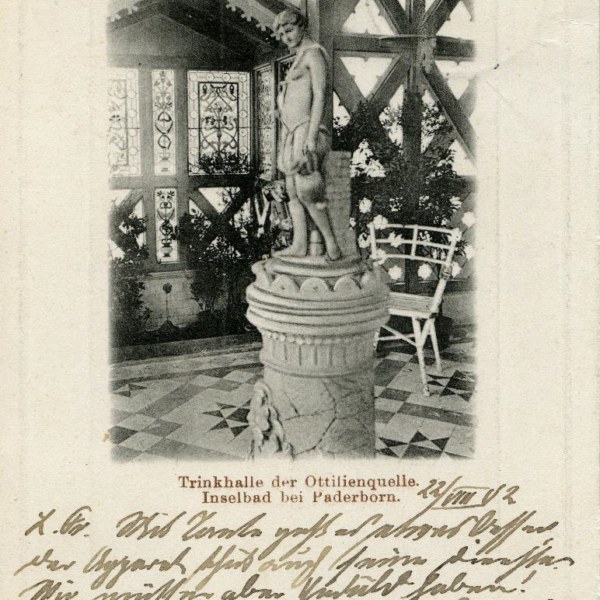

As early as the 16th century, the commercial use of six springs in the area between the Pader and the Rothebach is documented, which was called an „island“ early on due to its confinement by both bodies of water. On the one hand, the springs were said to have a healing effect, on the other hand they fed several fish ponds and thus contributed to the nutrition of the regional population.

Credit: „Die ehemalige Benedictiner Insel zwischen Paderborn und Neuhaus“ in the early 19th century, drawing by Franz Joseph BRAND (Archbishop's Academic Library, hereafter EAB PbAV Paderborn, Cod. 178, fol. 46)