[1] Cf. Börste/ Santel: Schloss Neuhaus, p. 75. Zu den technischen Details der Anlage vgl. die Baurechnung für das Jahr 1753. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 2r-29.

[2] In May 1754, Prince-Bishop Clemens August responded positively to the inquiry of his court architect Nagel: for all future repairs and technical improvements („melioration“) to the New Waterworks, „waßer Meister Rödel“ (water master Rödel) was to be commissioned. The Paderborn Court Chamber was to bear the costs incurred by this alone. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Nr. 3081, fol. 1r-1v.

[3] The large fountain in the gardens of Prince Bishop Clemens August was very probably not powered directly by the Old Waterworks „near the Paderborn Gate“. Vgl. Kandler/ Krieger/ Moser, Schloß Neuhaus, p. 48.

[4] Cf. Plan 2 „Ansicht des Schloßgartens zu Neuhaus von Philipp Sauer 1753 [um 1790]“, EAB Pb, AV, Akta 88, fol. 2r-3v.

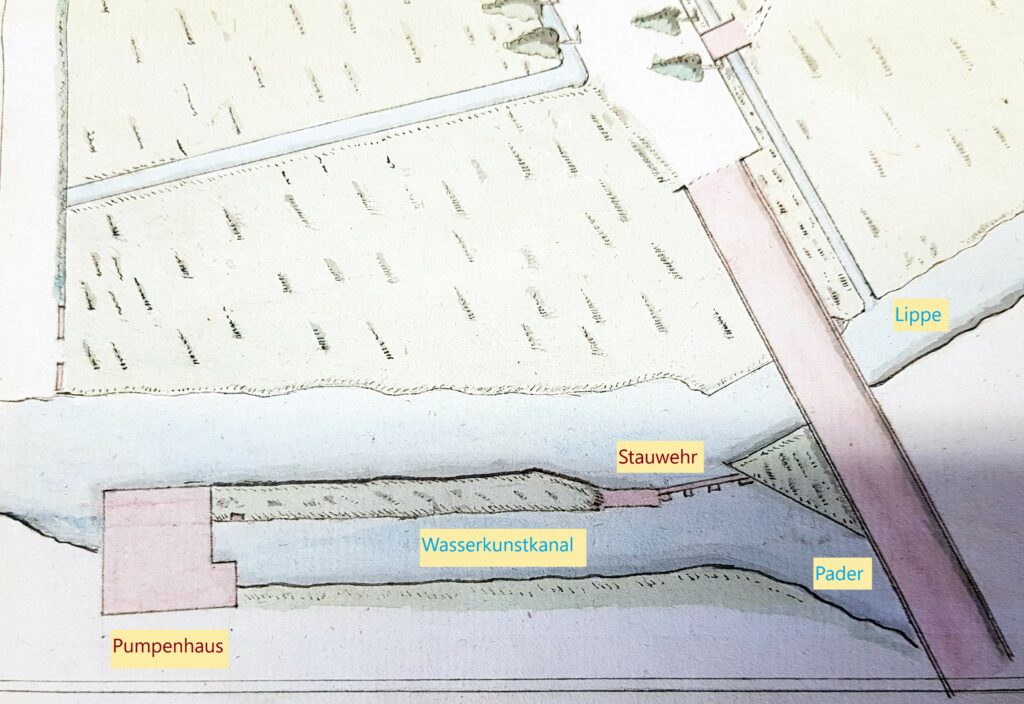

[5] Cf. Expert opinion by Franz Anton Becker for Prince-Bishop Franz Egon v. Fürstenberg, o. d. (1789?): „1mo: […] with the great water=works the drop of the Pader into the Lippe should be 28 inches after the vertical line“. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3044, fol. 33r-35v, here fol. 33r.

[6] Cf. „Grundriß des Gemüsegartens und der Wiesen im Schloßpark (18. Jhd.)“, EAB Pb, AV, Akta 88, fol. 14v-15r as well as „Grundriß der Wiese bei der Lippebrücke (18. Jh.)“, fol. 18r-19v.

[7] Cf. Börste/ Santel, Schloss Neuhaus, p. 77; Hansmann, Neuhäuser Schlossgarten, p. 132.

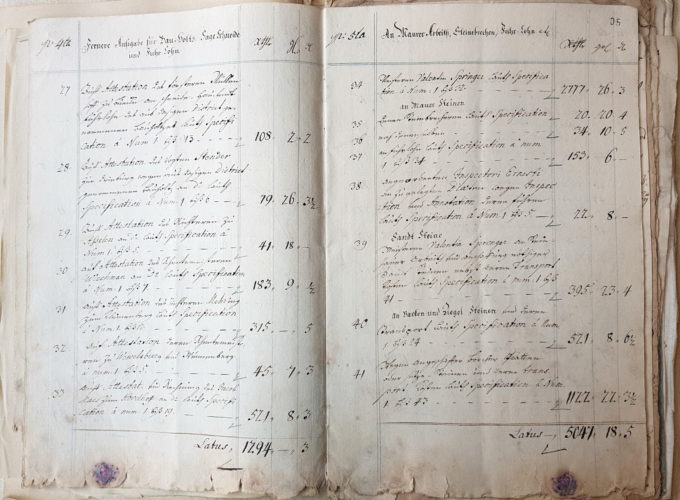

[8] Cf. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 5r-6r.

[9] Cf. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 4r ff.

[10] „Ahn Zimmer vnd Arbeitslohn behueff deren Caßellanern – 823 Rtl. […] behueff hiesiger Zimmerleuthen – 775 Rtl.“. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 4r.

[11] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 8v.

[12] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 7r.

[13] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 5v.

[14] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 9r. The total construction costs for the New Waterworks amounted to an estimated 23,000 Reichstaler. Vgl. Wurm, Neuhaus, Sp 58.

[15] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 8r.

[16] Cf. quotation by Ganzer, June 1808. StadtA Pb, A 888, fol. 29v-33v., here 33v.

[17] Baurechnung 1753: „[…] iron tubes transported from the Altenbecker Hütten hereto”. Cf. travel expenses of the electoral court blacksmith „Meister Johann“, who in June 1758 had the „large spigot […] forged to the great works“ at the hammer in Altenbeken. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 3v; 17r.

[18] Cf. Baurechnung 1753: „Auswerffung des erforderlichen Pott-Leimens – 104 Rtl.“ LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 4r.

[19] Cf. quotation by Ganzer, June 1808. StadtA Pb, A 888, fol. 29v-33v.

[20] Cf. Ströhmer, Michael: Die Paderborner Wasserkünste als technische Denkmale des europäischen Kulturerbes ECHY 2018, in: WZ 169 (2019), p. 295-317.

[21] Cf. Kanne, Familien in Neuhaus, p. 93; 109. In 1805, water master Eberlein lived with his second wife Gertrud Hille in a small half-timbered house in today’s „Sertürner Straße 26“.

[22] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 8r.

[23] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3054, fol. 26r. In October 1759, the Neuhaus „Wassermeister Cramer“ (water master Cramer) is to supervise the renovation work on the „Wasserleytung von Lippspringe bis an die Neuhäus. Fish Dikes“ (Water pipeline from Lippspringe to the Neuhaus fish dikes). Quoted from Pavlicic, Eine altertümliche Wasserzuleitung, p. 26.

[24] Cf. Flur V, Parz. 240 und 237.